Eager faces look up towards the intricately carved window where the living Goddess is about to make an appearance. Suddenly, a male face comes into view and requests for cameras to be put away. No one is allowed to photograph the Goddess. The swarm of tourists in the Kumari Ghar, guarded by white lion statues in Kathmandu’s Durbar Square, hastily put away their phones and cameras and snap into attention. A minute later, a young, unsmiling face of a girl child appears at the ornate window. A hush descends. Her sharply painted eyes briefly scan the crowd below and abruptly withdraws.

Someone whispers – “Why doesn’t she smile?”

Someone replies – “It is considered a bad omen if she does. But these unscheduled appearances will bring good fortune.”

That debate is settled, and tourists bow out. The Kumari Ghar with its stunning wooden pillars and windows reflecting the finest Newari art is empty again.

Like her, there are 11 other Kumaris all over Nepal, but the Kathmandu Kumari I have just seen is considered the Raj Kumari (royal) selected after a rigorous process and considered to possess 32 signs of divinity. She will remain in her position till she matures, and another Kumari will be selected to replace her. The Royal Kumari lives in the newly restored, three-storied Kumari Ghar, which was originally built in the eighteenth century by King Jaya Prakash Malla. It was restored to its current state in 1966.

Emerging into the Durbar Square, I feel a sense of elation having just witnessed Nepal’s most intriguing cultural tradition. The living goddess represents Taleju Bhawani, the patron deity of Newari Hindus in Kathmandu Valley. Legend has it that the ancient kings of Nepal were devotees of goddess Taleju and she would often visit the palace to play games of cards with the kings. An unfortunate incident left the goddess upset and she swore she would only appear in the form of a child or Kumari. Hence the tradition. And a unique one too.

Everlasting allure of Freak Street

Durbar Square, a Unesco World Heritage Site, is filled with crumbling temples, brick piles, majestic buildings and tourists. In one corner, women sell garlands of bright orange marigolds under sunshades, sharing space with stray dogs resting in the afternoon sun. There is chaos everywhere, but Kathmandu’s rich heritage shines through it all. There are over 50 temples in the Square (not all of them standing today), which also goes by the name of Museum of Temples and was the place where the kings were crowned and legitimised.

From here, I proceed to Jhochhen Tole, the erstwhile Freak Street that attracted travellers (hippies) in the 1960s who came in search of nirvana and mysticism in one of the many alleys and corner-shops off Durbar Square. Official signposts refer to this area as Jhochhen Tole, but the shop signs scream Freak Street. This name was given by locals when a huge number of ‘strange’ hippies congregated along the streets’ popular cafes.

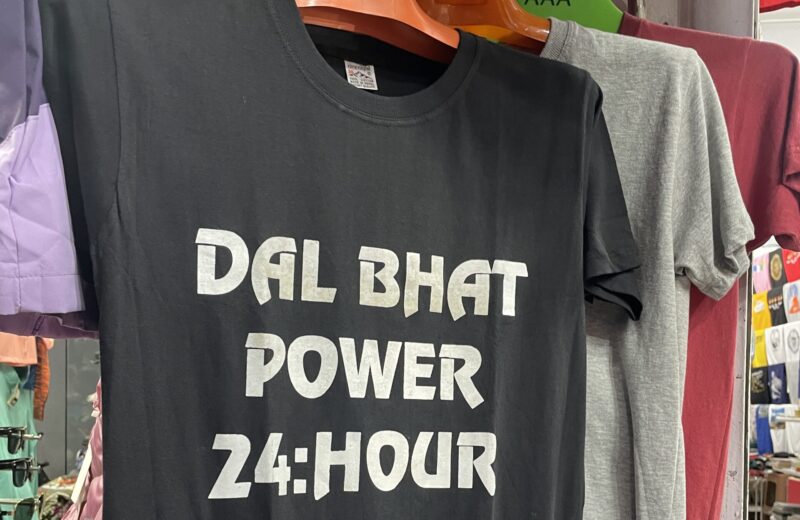

Truly, the old Kathmandu charm is still present here. People greet me out of friendliness and with no inclination to sell a souvenir. Somehow, it is quieter. A Tibetan mask centre, one of the last remaining face mask shops in the city, a second-hand bookstore pushing its limits to stay alive in the vanishing bookstore culture, nameless carpet, pashmina and local clothes store add to the charm of this street.

I seek out Snowman’s Cafe, now in a state of neglect, but which in the days of the hippie-culture was Freak Street’s most famous landmark and hosted the likes of Beatles and Cat Stevens. It holds the key to cultural changes that began in the 1960s with the arrival of the hippies who added an international vibe in this mystic, mountain-country.

I step into the Cafe which is filled with a young Nepali crowd and the odd tourist seeking out the best apple pie in Nepal via Lonely Planet guides. The interiors are dull brown and dimly lit, walls are covered with writings, messages and yellowing picture frames. The owner with his flowing white hair gingerly cuts out a slice of apple cake, fixes a coffee from a machine and smiles warmly at me. I urge him to speak of his youth, but he merely mumbles and turns away. The pie is deliciously sweet and moist and goes well with the bitter black coffee. I sip in silence, trying to visualise how this now-obscure cafe welcomed the Flower Children in the 60s and 70s and became synonymous with the modern-Kathmandu. It was here, among other places, that travellers networked with each other as they journeyed east and west.

It is hard to imagine this street with its smooth stone slabs and guesthouses had inspired Cat Stevens to write his famous song Katmandu.

Bhaktapur’s King Curd

Time is on my side, but Kathmandu’s infamous traffic snarl slows my journey to Bhaktapur, another Unesco World Heritage Site about 13 kilometres from the capital. Once the country’s national capital, the historic heart of Bhaktapur feels transplanted from the Middle Ages. The intricate woodwork of its temples, gates, museums, and palace surrounding the Durbar Square is stunning.

It is said that the first palace in the current Durbar area was built by King Jayasthiti Malla, in the late 13th century, but there are no remains left of the original palace.

Bhaktapur, designated as an open museum, is less chaotic than its Kathmandu counterpart and slightly more relaxing. A few buildings are undergoing renovation, following the devastating earthquake that caused massive destructions. (Durbar refers to the area opposite the old royal palaces in Nepal). I head to the northern alley after Bhandarkha Chowk, that leads to the National Art Museum – where sculptures from the Malla and Licchavi periods are being treasured.

View this post on Instagram

It is then I notice people seated on the temple stairs, enjoying something from a claypot or a kataaro. My curiosity leads me to a small shop outside the Durbar Square where I discover the juju dhau and its fascinating history and taste.

Juju Dhau (translates to King of Curd) dates back over 2,000 years and is deeply rooted in Bhaktapur’s Newar community. Its traditional recipe is closely guarded. Story has it that kings of the Malla period once organised a curd competition. Curd-makers from Kathmandu, Bhaktapur and Lalitpur participated, but the king liked the curd of Bhaktapur. From that day, the curd of Bhaktapur came to be known as Juju Dhau. Eventually, it was developed as a sacred offering for festivals and evolved into a ceremonial delicacy, soon becoming a symbol of Bhaktapur’s culinary excellence and cultural identity. Juju dhau is eaten when a person is leaving home and to purify oneself during fasting days and is kept on doorways to bring good luck.

It looks like a custard and even has a similar consistency. But in Newari culture, it holds top position as one of the five culturally significant nectars together with milk, sugar, honey, and ghee, representing hope and good luck.

For NPR 60, I get a small kataaro of juju dhau. There was a bubbly skin on top. With my tiny wooden spoon, I push through the skin. The spoon sinks into the creamy curd.

I put a spoonful into my mouth. The tang of curd is delicately masked by a subtle sweetness. In that instant, I taste centuries of Newari culture. The young, unsmiling face of the Raj Kumari flashes in my mind, the mystic charm of the Freak Street explodes in my heart and hope fills my soul.